Contributor: Liz Stiverson

Work and Life is a two-hour radio program hosted by Stew Friedman, director of the Wharton Work/Life Integration Project, on Sirius XM’s Channel 111, Business Radio Powered by The Wharton School. Every Tuesday from 7 to 9 PM EST, Stew speaks with everyday people and the world’s leading experts about creating harmony among work, home, community and the private self (mind, body and spirit).

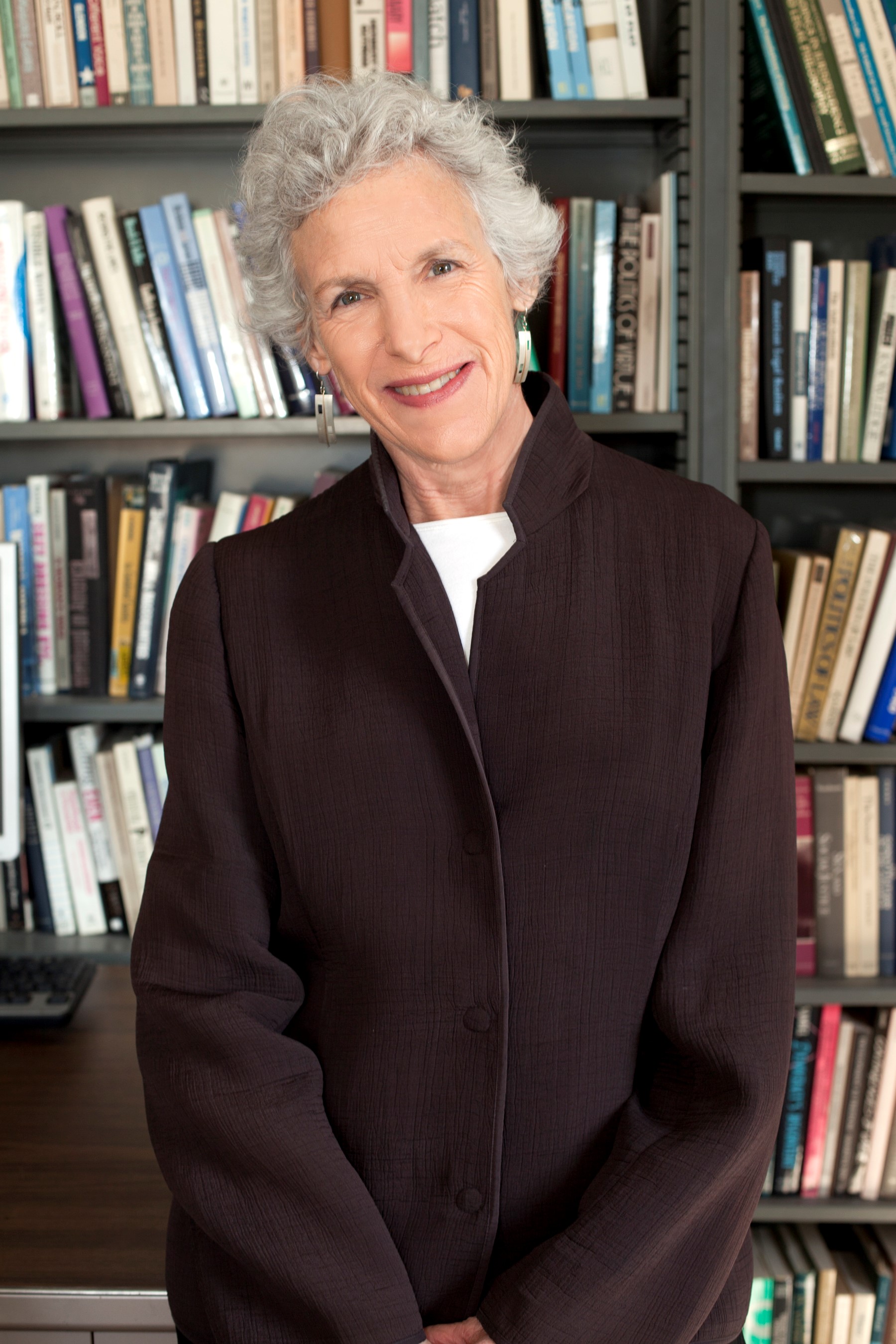

On Work and Life, Stew Friedman spoke with Anne-Marie Slaughter – author of the ground-breaking 2012 Atlantic article “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” which sparked a national debate about the real pressures of having a career while also serving as a caregiver at home – about a traditional gender bias that underlies the American work-life conflict and the conversation we need to have in order to move forward.

The following are edited excerpts of their conversation.

Stew Friedman: What has changed in your consciousness and perspective in the two years since you wrote your article for The Atlantic?

Anne-Marie Slaughter:  A couple of things have changed. When I wrote that article, I started out with the same question Sheryl Sandberg asked, which was, why are there not enough women at the top? Over time, I became increasingly convinced that that question was actually only one part of a two-part question, and it was very important to consider the two parts together. The other part of the question is, why are there so many women at the bottom? Rather than seeing a divide between privileged, elite women and poor women, I came to see those two questions as part of the same issue. It became increasingly evident to me that, in fact, the answer to both of those questions is that as a society, we don’t value care and care-giving. We say we do, but in reality, people who take time out of their careers to give care pay a real price for it. If you take time out from other kinds of work to give care, your career will be penalized. That’s why we see a huge drop-off in women on the leadership track during their child-bearing years. And if you are the sole care-giver and bread-winner, supporting your family and giving care at the same time, you are much more likely to be at the bottom.

A couple of things have changed. When I wrote that article, I started out with the same question Sheryl Sandberg asked, which was, why are there not enough women at the top? Over time, I became increasingly convinced that that question was actually only one part of a two-part question, and it was very important to consider the two parts together. The other part of the question is, why are there so many women at the bottom? Rather than seeing a divide between privileged, elite women and poor women, I came to see those two questions as part of the same issue. It became increasingly evident to me that, in fact, the answer to both of those questions is that as a society, we don’t value care and care-giving. We say we do, but in reality, people who take time out of their careers to give care pay a real price for it. If you take time out from other kinds of work to give care, your career will be penalized. That’s why we see a huge drop-off in women on the leadership track during their child-bearing years. And if you are the sole care-giver and bread-winner, supporting your family and giving care at the same time, you are much more likely to be at the bottom.

SF: It also affects people in the labor market. Childcare workers are among the lowest paid people in our country. I say the closer you are to a diaper – at the beginning or end of life – the less you are valued in society.

AMS: That’s absolutely another dimension of this. If you’re doing care-giving work as paid work, you are neither well-paid nor well-respected.

This really shook me up as a feminist. I realized that I had been raised as a feminist, proudly, to think that the work my father did was much more important than the work my mother did. I thought that the way I was going to be somebody in the world was not to do what my mother did – she was a stay-at-home mother and later a superb artist — but primarily defined herself as a wife and a mother. It was obvious to me that I should want to be a professional, because that was “more important” than care work. Realizing this, I had to say, “Wait a minute – that can’t be true.” If men and women are really equal, then the kinds of work we’ve traditionally done has to be equal, too. It can’t just be that we’re equal as long as we all act like men. Most women of my generation, whatever they say, do not think a stay-at-home mom does work that is as important as being the CEO of a think tank, for example. It’s uncomfortable to admit, but that’s just not what we were raised with. And this recognition of the equal value of different kinds of work is not just important for women – it’s vital for men as well. In the end, we are going to need an equal number of people in the workplace and in the home, supporting different kinds of work. If a woman is a CEO, she’s going to need someone at home who is what I call the lead parent, or the flexible caregiver, depending on who is being cared for. The only way to achieve that is to truly value care-giving, and to value it when men do it as well as when women do it.

SF: Yes, absolutely. What have you discovered and what are you advocating for so that we as a society can truly value care-giving?

AMS: The first thing we need is to break this conversation open. When I wrote my article, there were a lot of women thinking, “Everybody just says make it work, do it all, have it all; I’m supposed to be able to be at the top in my career and be a caregiver, but actually, this is really hard, and no one wants to admit it.” Well, we broke that conversation open. I think similarly, we really have to have a conversation that exposes looming biases. Few people will say openly, “Well no, of course care-giving is not as important as being a professor, or a lawyer, or a factory worker, or anything else,” but that’s what they think. Instead, we have to bring that out and look at it. Taking care of children is investing in the human capital of the next generation. There’s actually nothing more important that we do as a society, and if we do it badly, we pay for it economically, socially, criminally, and morally, in the sense of wasted lives and potential.

SF: And we’re not doing well compared to other developed nations.

AMS: Absolutely. And taking care of elders is an affirmation of our common humanity – a recognition that we will all be there someday. As well as making people’s lives longer and better, it’s a basic commitment to human dignity. Skilled care-giving requires education and experience, and we have to recognize that it’s something we should be valuing every bit as much as we value lending money or drawing up a will.

Anne-Marie Slaughter was the Director of Policy Planning for the U.S. State Department under Hilary Clinton, and is now the President and CEO of The New America Foundation, a non-profit, non-partisan public policy institute addressing the next generation of challenges facing the U.S. New America is actively working on issues of bread-winning and care-giving (their more gender-neutral term for family and workforce topics) including cross-generational engagement through technology and the future of higher education after college to enable lifelong learning from multiple sources. Learn more at New America’s website. For more from Slaughter, follow her on Twitter @SlaughterAM.

Join Work and Life next Tuesday, June 3 at 7 pm on Sirius XM Channel 111 for conversations with Shannon Schuyler, Principal and Corporate Responsibility leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers, and Liza Mundy, author of The Richer Sex: How the New Majority of Female Breadwinners is Transforming Our Culture. Visit Work and Life for a full schedule of future guests.

About the Author:

Liz Stiverson  received her MBA from The Wharton School in 2014.

received her MBA from The Wharton School in 2014.

I think that’s an interesting example of a well-documented trend in international studies. At a certain point after women enter the workforce in large numbers, the national fertility rate tends to drop. Social conservatives in the United States have suggested that if as a society we don’t make childcare easily available, women will be forced from the workplace and go back to having babies, but evidence suggests that the opposite is actually true. When you make it harder for women to combine work and family, women don’t start families. If you want, as a society, to have more kids, you need to make it easier for women to combine work and family. Countries like France and Sweden are doing better in terms of maintaining fertility because they have instituted such polices.

I think that’s an interesting example of a well-documented trend in international studies. At a certain point after women enter the workforce in large numbers, the national fertility rate tends to drop. Social conservatives in the United States have suggested that if as a society we don’t make childcare easily available, women will be forced from the workplace and go back to having babies, but evidence suggests that the opposite is actually true. When you make it harder for women to combine work and family, women don’t start families. If you want, as a society, to have more kids, you need to make it easier for women to combine work and family. Countries like France and Sweden are doing better in terms of maintaining fertility because they have instituted such polices. One pattern of gender bias that really plays into work-family conflict is that women often feel that they have to prove themselves over and over again, providing much more evidence of competence than their male colleagues in order to be perceived as equally competent. Women’s successes are more likely to be attributed to luck rather than skill. In our interviews, we heard women over and over again feeling that men were judged on potential while women were judged strictly on performance. Because of this, women often feel that they literally have to work harder than men in order to be seen as equally competent, especially since women’s mistakes tend to be noticed more and remembered longer.

One pattern of gender bias that really plays into work-family conflict is that women often feel that they have to prove themselves over and over again, providing much more evidence of competence than their male colleagues in order to be perceived as equally competent. Women’s successes are more likely to be attributed to luck rather than skill. In our interviews, we heard women over and over again feeling that men were judged on potential while women were judged strictly on performance. Because of this, women often feel that they literally have to work harder than men in order to be seen as equally competent, especially since women’s mistakes tend to be noticed more and remembered longer. Alice Liu is an undergraduate senior studying Management at The Wharton School and English (Creative Writing) at the College of Arts & Sciences.

Alice Liu is an undergraduate senior studying Management at The Wharton School and English (Creative Writing) at the College of Arts & Sciences.  For me it was about career progression. I was at a certain level in my career where I was ready to make the next move, and I wanted to make sure that I had the best education possible to help me get to that next level.

For me it was about career progression. I was at a certain level in my career where I was ready to make the next move, and I wanted to make sure that I had the best education possible to help me get to that next level. SF: Who are the important people – the key sponsors or mentors – who have influenced you and helped you get here?

SF: Who are the important people – the key sponsors or mentors – who have influenced you and helped you get here? Alice Liu is an undergraduate senior studying Management at The Wharton School and English (Creative Writing) at the College of Arts & Sciences.

Alice Liu is an undergraduate senior studying Management at The Wharton School and English (Creative Writing) at the College of Arts & Sciences.  Jessica DeGroot founded

Jessica DeGroot founded  On

On  On

On  Kate Mesrobian is a sophomore in the Huntsman Program in Business and International Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Kate Mesrobian is a sophomore in the Huntsman Program in Business and International Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Alice Liu is an undergraduate senior studying Management at The Wharton School and English (Creative Writing) at the College of Arts & Sciences.

Alice Liu is an undergraduate senior studying Management at The Wharton School and English (Creative Writing) at the College of Arts & Sciences.

Sharon Meers is the Head of Enterprise Strategy at Magento, which is part of eBay Inc. Prior to joining eBay, Sharon was a Managing Director at Goldman Sachs. Joanna Strober is the Founder and CEO of an online company to help fight and prevent childhood obesity. Together they have written

Sharon Meers is the Head of Enterprise Strategy at Magento, which is part of eBay Inc. Prior to joining eBay, Sharon was a Managing Director at Goldman Sachs. Joanna Strober is the Founder and CEO of an online company to help fight and prevent childhood obesity. Together they have written